By: Robin Llewellyn

The families sang in their shelter in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, unaware of their attackers closing in around them.

Those who would kill them would later say their naked victims had “sung like the monkeys sing… The song seems like it’s calling the jungle… It was like the voices of the animals; they sung strong, strong…”

The singers were from the Taromenane tribe, an indigenous group who avoid contact with the outside world. Despite being protected by the Ecuadorian Constitution as an “uncontacted people” decades of attacks against them had reduced their numbers to between less than 150 up to 300 people, who live in small groups in the Yasuni National Park above the few untapped oil reserves left in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Their attackers were from the Waorani tribe, another indigenous people who were “contacted” during the initial colonization of the vast Ecuadorian jungle and who often live in roadside communities integrated into the petroleum economy of the Amazonian frontier.

These 15 Waorani warriors carried pistols, shotguns, and ammunition newly purchased from the petroleum boomtowns of Coca and Lago Agrio and possessed smartphones to photograph the aftermath of the massacre.

These men were on a mission to revenge the death of the Waorani elder Ompure Omewey and his wife Buganey, who were assassinated by the Taromenane tribe three weeks earlier on the 5th of March, inside Spanish oil giant RepSol’s Petroleum Block 16.

The Taromenane are known to kill all “cowori” or outsiders who enter their territory and over the decades the bodies of illegal-loggers and hunters impaled by spears have been found around the border of their nomadic hunting grounds. The targeted assassination against the Waorani elder Ompure however was remarkable not only because the killing occurred in the heart of RepSol controlled Block 16 but because Ompure was known to them.

Ompure Omewey’s “first contact” with the Taromenane tribe

Ompure was a bridge between the worlds of the contacted and uncontacted; the only person to survive multiple peaceful interactions with the Taromenane. The elder described his first contact with the Taromenane in this video almost a year to the day before his death:

The Taromenane had asked him to keep the encroaching outsiders away from their lands. The Taromenane also said they were too terrified to leave their cover to cross the Via Maxus, an “oil highway” cut through the jungle by the Maxus Oil Company, who along with Texaco and state-run PetroEcuador have led the opening of the Amazonian frontier.

The final frontier for petrol companies in the Ecuadorian Amazon is the Yasuni National Park, which consists of Taromenane territory known as the “Intangible Zone” because in 1991 a presidential decree declared it untouchable due to its: “great cultural and biological importance in which no type of extractive activity can be carried out due to the high value they have for the Amazon region, Ecuador, the world, and present and future generations.”

Ecuador’s 2008 Constitution went one step further to protect its uncontacted peoples stating:

“The territories of the peoples living in voluntary isolation are an irreducible and intangible ancestral possession and all forms of extractive activities shall be forbidden there. The State shall adopt measures to guarantee their lives, enforce respect for self-determination and the will to remain in isolation and to ensure observance of their rights. The violation of these rights shall constitute a crime of ethnocide, which shall be classified as such by law.”

Ecuador’s greatest oil reserve is the Yasuní-ITT field, inside the Yasuni National Park overlapping the Intangible Zone, and Rafael Correa’s government initially pledged to seek international donations to leave the oil underground as part of its ‘Yasuní Initiative’.

The initiative was first promoted at the governmental level by the Ministry of Energy and Mines, but opposed by the powerful chief executive of Petroecuador, who was determined to extract the reserve’s estimated 900 million barrels of heavy crude.

The initiative was first promoted at the governmental level by the Ministry of Energy and Mines, but opposed by the powerful chief executive of Petroecuador, who was determined to extract the reserve’s estimated 900 million barrels of heavy crude.

President Correa told the board of Petroecuador on 31 March 2007 that the government would consider extracting Yasuni’s oil as “Option B” if international funds were not forthcoming to keep the oil underground.

According to former Minister of Energy and Mines Alberto Acosta, “those mandated with the project did not tire of threatening the imminent exploitation of the ITT field in Yasuni, in fact [it was] more than a threat, it was a demonstrated certainty with the advancement of extractive activities in Block 31, adjacent to ITT”.

While the Government referred to the plight of the uncontacted tribes in the Yasuni to boost international donations, the full extent of the Taromenane’s land was, at the time, still not immune from exploration.

Both Block 31 and the oil concession of the Yasuní-ITT oil reserve (‘Block 43’) overlap the Taromenane tribe’s Intangible Zone.

Both Block 31 and the oil concession of the Yasuní-ITT oil reserve (‘Block 43’) overlap the Taromenane tribe’s Intangible Zone.

Petroleum Block 16 that borders Block 31 overlaps a 10 km deep buffer zone surrounding the land of these uncontacted peoples, in which forestry and mining is legally prohibited.

As the years past and the petrol companies closed in on the Intangible Zone, the Taromenane made their complaints known to Ompure. The tribe also requested the Waorani elder supply them with cooking pots, machetes, and modern tools. Ompure reportedly petitioned RepSol, who operates Block 16, to supply the Taromenane with tools but the Spanish company refused him. Repsol denied to confirm this citing on-going court processes, but following Ompure’s murder the Spanish company’s staff were evacuated from the area.

Waorani hunt Taromenane while Government hunts oil

In the 19 days following the assassination the 15 Waorani warriors had not kept their intentions for revenge secret. They purchased weapons and ammunition to kill the Taromenane while the very government officials responsible for a Precautionary Measures Plan for the Protection of the Tagaeri Taromenane People were in Quito taking workshops with consultants on the issue of the sale of weapons and ammunition in the Amazon.

The world’s leading authority on Ecuador’s uncontacted tribes, Spanish Capuchin priest Miguel Cabodevilla, repeatedly petitioned the Ministry of the Interior to intervene in the impending massacre. The government-owned newspaper El Telegrafo condemned such requests as blackmail.

[quote]Then while the heavily-armed Waorani scoured the jungle to exterminate the Taromenane, leading Ecuadorian officials were in Beijing soliciting bids for new petrol concessions in its Amazon.[/quote]The government’s boosting of public spending to unprecedented levels is largely financed by Chinese loans exchanged for oil concessions – Quito now exports around 90% of its petrol to China and owes the Asian superpower US$4.71 billion (as of April 2014).

On the morning of the 30th of March the Waorani warriors found a deserted Taromenane house, and the multitude of photographs taken testifies to their mounting excitement after days searching in the jungle. Later that day they found the skulls of wild pigs eaten by the uncontacted tribe, and by mid-afternoon they heard the Taromenane singing. Stealthily they approached the thatched hut, anxious not to alert the two guards stationed at the doorway.

As a Taromenane boy and girl walked out of the hut they discovered the ambush the boy fled indoors, the song abruptly stopped and spears rattled inside the hut. The men of the uncontacted tribe burst out to fight and defend their women and children so they could flee “But bullets are faster than spears” recalled one of the Waorani attackers.

“The rifles didn’t sound loud” one said Waorani, “lots of blood came out, lots of blood, blood dripping like water… We killed each one with a gunshot, we shot them without stopping”.

In the jungle, the Waorani warriors impaled the heads of two men onto stakes and then when they had “finished with killing”, they entered the hut and consumed the food and fermented drink called chicha that the Taromenane had been preparing. Inside the thatched building they found some of Ompure’s possessions which justified in their minds the massacre.

A bewildered Taromenane mother came to the hut after seeing the carnage and begged the warriors for mercy pledging herself to become the wife of the warrior who spared their lives. The raiders impaled her on a spear in front of her daughters then debated what to do with the 6 and 4 year old girls.

As the debate heated up and as one Waorani took trophy photographs of the bodies of men, women, and children riddled with bullets and impaled by spears. A body moved startling the warriors and they fled with the two Taromenane girls.

Even though members of the revenge mission began selling the photographs on the streets of Coca and one even appeared on the program Day to Day on TeleAmazonas confessing killing 5 people with spears. “I killed!” he said, “because i’m a warrior”. Government officials however outwardly seemed surprised about the ‘alleged’ massacre expressing doubt as to whether it actually happened citing a lack of ‘tangible evidence’ and the ‘unattributed’ nature of the photographs.

Two parliamentarians wrote to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights informing them of the attack and reminding them of Ecuador’s obligations under the Precautionary Measures imposed by the Commission to protect the Taromenane against attacks by Waorani and loggers. [quote]The parliamentarians said that by allowing oil extraction, the government was creating the conditions for the physical and cultural extinction of the uncontacted indigenous.

[/quote]

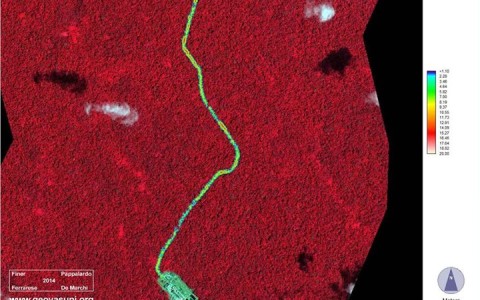

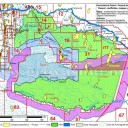

In response Quito filed a report on the state’s compliance with the Inter-American Commission’s Precautionary Measures in April 2013. It depicted the uncontacted peoples via circles on a map, the four groups inhabiting areas in or bordering the ‘intangible area’ and extending into the adjoining oil blocks 16, 31, and ITT.

One of the circles represented the ‘Grupo Via Maxus’, centred around the Waorani community of Yarentaro, spreading into Blocks 14 and 16 and the area of the Via Maxus.

The public prosecutor’s office however would not visit the site of the massacre, where at least 20 – 30 men, women, and children were slaughtered for another 9 months. The investigation went dormant and after the initial flurry of news articles in the aftermath the Ecuadorian press were also silent.

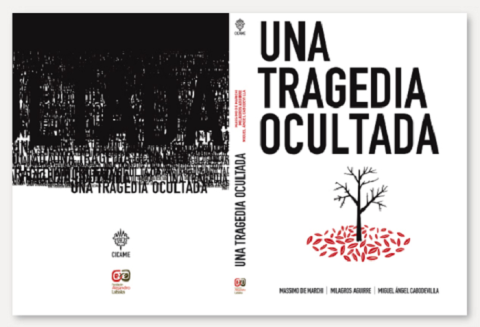

Meanwhile Milagros Aguirre and Miguel Cabodevilla initiated their own investigation and documented their findings in the book ‘Una Tragedia Ocultada’ (we have translation large section of the book here). The book meticulously details government incompetence with their obligations under the Precautionary Measures to protect uncontacted peoples. The Waorani expedition into the jungle was related through first person testimonies and photos taken on the raid as well as reports off airdrops of poisoned food were also documented.

Rewriting the Constitution to Change Definition of Genocide

The members of the 2007 ‘Constitutional Assembly of Montecristi’ convened again to rewrite a new Constitution that suspended the sitting Congress for representing what they believed were the corrupt, elitist old order. In drafting the new Constitution they promoted it as a “Citizens Revolution” where the citizens themselves would now govern Ecuador, by being able to overturn unpopular decisions by the government if the citizens collected enough signatures to force a national referendum.

While the extraction of resources were still banned on lands inhabited by uncontacted tribes, President Correa emphasized the need to reinterpret the new constitution ‘in good faith’ stressing the importance of securing mineral and petrol wealth and to modernize the economy. Correa’s supporters claim that using Chinese loans to boost spending in return for oil is a revolutionary form of ‘south-south’ cooperation that will wean Ecuador from colonial patterns of trade.

In August 2013 another map was sent by President Correa to the National Assembly as he sought their approval to open the Yasuní-ITT field to exploration. Now they declared that there were only three uncontacted tribes in the region: the Via Maxus group had disappeared. The three other groups including the Taromenane were now located outside the Blocks Yasuní-ITT and 31.

The government was faced with the constitutional injunction of exploration in areas inhabited by uncontacted tribes, and selectively quoted elements of the UN’s Draft Guidelines on the Protection of Indigenous People Living in Voluntary Isolation and in Danger of Extinction to argue that oil exploration would not equate to ethnocide.

Basque lawyer Mikel Berraondo, who drafted these UN guidelines that the Ecuadorian executive had selectively quoted, said everything in his work that opposed the exploitation of Yasuní-ITT was ignored. He described the government’s actions ‘Machiavellian’: “It is an insult to the intelligence of the people that someone can place a report before a congress of such importance as a national parliamentary assembly, and believe that no one in this country will realize the deceit in this report.”[pullquote]“It is an insult to the intelligence of the people that someone can place a report before a congress of such importance as a national parliamentary assembly, and believe that no one in this country will realize the deceit in this report.”

– Mikel Berraondo[/pullquote]

The government also submitted maps to Congress created by the Ministry of Justice, which sought to argue that uncontacted tribes were neither living in, nor passing through Blocks 31 and 43. They argued that altitude and geography made the area an unlikely home for the Taromenane, and cited the lack of sightings of uncontacted peoples by camera traps.

“The Ministry can say what they want; I say what I think as a scientist.” says Italian geographer Massimo Marchi, an expert on the Ecuadorian Amazon, “I’m a university professor; if the Ministry’s briefing was submitted there it would not have passed the exam, because there was no scientific consistency.”

The altitudes cited in the document were one of many errors, he said; such altitudes would have resulted in the blocks being underneath a subterranean lagoon stretching to Peru.

On the 24th of September, 17 minutes before Milagros Aguirre and Cabodevilla’s book A Hidden Tragedy was due to be released, it was prohibited to circulate over any medium. The censorship backfired and the book was shared far and wide for free over social media which consequently transformed the public profile of the massacre, ensuring a widespread distrust of the government’s stewardship of oil exploration. On 3 October 2013 the National Assembly voted to allow oil exploration in Blocks 31 and the Yasuní-ITT field (Block 43).

[quote]Eight weeks later, the government adjusted the laws on genocide and ethnocide, changing the definition of the crimes. The crimes now needed to involve the intention to destroy a people or a way of life. The extinction of the Ecuadorian Amazon’s last uncontacted peoples due to the collateral damage of oil extraction was no longer considered a crime.[/quote]

These changes were presented to the National Assembly by the ruling party’s Mauro Andino, who said their authorship ‘corresponded to a great visionary, revolutionary and patriot’ (President Rafael Correa). Seven of the Waorani warriors responsible for the massacre were then arrested under the new legislation for acts of genocide and their cases passed to the Constitutional Court.

To Milagros Aguirre, when the government avoided their obligations under Precautionary Measures by refusing to pay the Waorani compensation for the assassination of Ompure, their warriors acted according to the traditions of the Amazon, as soldiers in a war. The prosecutions of the Waorani after 10 months of inaction promised only “justice with a greater injustice; the Waorani are prisoners, their families suffer without their suppliers and hunters, hungry and suffering.”

Meanwhile the state “has no protocols in case of sighting human groups in the jungle, it has no mechanism to actually implement the Precautionary Measures, it has not provided education to the Waorani groups and it continues operating on their territory.”

To Carlos Andres Vera, who directed the 2007 documentary Taromenani, the Exterminaton of the Uncontacted Peoples, the culpability for the destruction of the Taromenane is clear: [pullquote]“So, according to the Constitution, the government is committing genocide. That´s why the second fact is important: they changed the definition of genocide in the new law, breaking the meaning and spirit of the Constitution.”

– Carlos Andres Vera[/pullquote]

“According to the Constitution, Article 57 says any activity regarding exploitation of natural resources is considered genocide. I agree with that definition. So, according to the Constitution, the government is committing genocide. That´s why the second fact is important: they changed the definition of genocide in the new law, breaking the meaning and spirit of the Constitution.”

The abandonment of the Yasuni initiative was resisted by an alliance of youth volunteers, who came together under the umbrella of Yasunidos.

Electoral Fraud Damages Credibility of Correas’ Citizen Revolution

They put to test President Correa’s flagship tool for direct democracy in his so-called Citizens Revolution by criss-crossing the country collecting hundreds of thousands of signatures to force a Popular Vote on whether to drill in the Yasuni.

On 12 April the Waorani leader Alicia Cahuilla presented the first box of 757,623 signatures against oil drilling to the National Electoral College (NCE) and force a national referendum.

The president of the National Electoral College (NCE) had previously spoken out in favour of oil exploration in Yasuní, and there was alarm when it was discovered that the boxes of signatures were being tampered with. The NCE subsequently invalidated 66% of the signatures under incredibly dubious circumstances and halted the referendum.

A subsequent investigation by Quito’s Universidad Andina Simon Bolivar studied 20,064 of the signatures and estimated that 673,863 of the total collected by Yasunidos were valid. The verification study estimated the margin for error at 0.76%.

To Alberto Acosta, who served as President of the Constitutional Assembly, the invalidation of over 650,000 signatures of people around Ecuador was further evidence that the core aim of Correa’s presidency was “the modernization of Ecuadorian capitalism”.

The Inter-American Court for Human Rights meanwhile ordered the reuniting of the two Taromenane girls, who remain separated, one in Orellana, the other in Pastaza. Of the two girl’s family little is known.

There are rumours that Taromenane spears have been thrown at oil company cars using a secret 26 metre-wide new highway cut by PetroAmazonas into Block 31, but they now evade contact.

On 22 May 2014 Ecuador approved a license for oil drilling in Block 43 inside the Yasuni National Park to Petroamazonas, with extraction expected to commence as soon as 2016. By then we may have found out that the Taromanene tribe, like the uncontacted via Maxus group before them, will have disappeared from maps of the Ecuadorian Amazon drawn up by the government of Rafael Correa.

[sexy_author_bio]

A raíz de sus circunstancias, 28 bandas de Punk Rock en Medellín organizaron un concierto llamado

A raíz de sus circunstancias, 28 bandas de Punk Rock en Medellín organizaron un concierto llamado

Pero eso no significa que Luis puede dejar de ser un camello, o camellar como dicen en Colombia, cuando de trabajo se trate o de rebuscarse el día a día para conseguir moneditas.

Pero eso no significa que Luis puede dejar de ser un camello, o camellar como dicen en Colombia, cuando de trabajo se trate o de rebuscarse el día a día para conseguir moneditas.

Alrededor del mundo – desde el primer

Alrededor del mundo – desde el primer

Un reciente informe de antropólogos ecuatorianos señala que existen en el Parque Yasuní al menos cuatro grupos aislados, mientras que otros análisis mencionan hasta siete.

Un reciente informe de antropólogos ecuatorianos señala que existen en el Parque Yasuní al menos cuatro grupos aislados, mientras que otros análisis mencionan hasta siete.

Frente al racismo se suma la discriminación y la pobreza en la que se desenvuelven, principalmente por la carencia de servicios básicos como agua potable, alcantarillado, servicios higiénicos, educación, salud, mas no por la tecnología que es muy accesible a estos grupos, no es raro verlos con un teléfono de última generación y sin agua limpia para beber.

Frente al racismo se suma la discriminación y la pobreza en la que se desenvuelven, principalmente por la carencia de servicios básicos como agua potable, alcantarillado, servicios higiénicos, educación, salud, mas no por la tecnología que es muy accesible a estos grupos, no es raro verlos con un teléfono de última generación y sin agua limpia para beber.

En muchos poblados indígenas este “consentimiento” se ha conseguido a la fuerza, con engaños, regalos suntuosos y, mentiras. Este “consentimiento” no tendría validez alguna y seria una clara violación del derecho a ser consultados, además que el consentimiento debe ser dado por la mayoría de los pobladores y, no como sucede en muchos casos donde solo firma un documento el dirigente a cambio de un “favor”

En muchos poblados indígenas este “consentimiento” se ha conseguido a la fuerza, con engaños, regalos suntuosos y, mentiras. Este “consentimiento” no tendría validez alguna y seria una clara violación del derecho a ser consultados, además que el consentimiento debe ser dado por la mayoría de los pobladores y, no como sucede en muchos casos donde solo firma un documento el dirigente a cambio de un “favor”

![Waorani in the initial stages of contact [photographer unknown]](http://www.chekhovskalashnikov.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/huaorani-tribe-spears1.jpg)

The establishment of homogenous states where everybody speaks a single language, receives standardized education, and live similar conformist lifestyles is one of the victories of capitalism ending the kind of cultures that oppose their system.

The establishment of homogenous states where everybody speaks a single language, receives standardized education, and live similar conformist lifestyles is one of the victories of capitalism ending the kind of cultures that oppose their system. Here we must clarify that the right of self-determination for uncontacted tribes means protecting their territory by preventing exploitation and not because there exists a zone declared intangible, which is to say that we must see the right to life of these people, the IUS COGENS.

Here we must clarify that the right of self-determination for uncontacted tribes means protecting their territory by preventing exploitation and not because there exists a zone declared intangible, which is to say that we must see the right to life of these people, the IUS COGENS.

Before dawn 12 hours earlier a man they call Pacho from the nearby town of Paipa rigs his car with a speaker and microphone transforming it into a mobile soapbox.

Before dawn 12 hours earlier a man they call Pacho from the nearby town of Paipa rigs his car with a speaker and microphone transforming it into a mobile soapbox. Over the following decades everything from contraband Ecuadorian potatoes to European imports of powdered milk made it harder for Boyacenses to do business.

Over the following decades everything from contraband Ecuadorian potatoes to European imports of powdered milk made it harder for Boyacenses to do business. Three paperos or potato farmers come to greet us, “this land makes good potatoes but what kills us are the importations, they don’t let us compete and now we are broke” says community leader Alexander Camargo.

Three paperos or potato farmers come to greet us, “this land makes good potatoes but what kills us are the importations, they don’t let us compete and now we are broke” says community leader Alexander Camargo. “When the government took the barley off us we had to look for a different crop, some went for potatos, others for milk or onions,” says Wilson Pulido a representative for the region.

“When the government took the barley off us we had to look for a different crop, some went for potatos, others for milk or onions,” says Wilson Pulido a representative for the region.