Its not every Sunday that the priest of a rural Colombian city called Tunja begins his sermon with a story of an illiterate Indian girl who grew up in the shadow of the British Empire.

The 8th of September was not a normal Sunday.

For the three weeks previous farmers from the province of Boyaca and its capital Tunja had blocked the roads to strangle the food supply en route to Colombia’s biggest city Bogotá.

Boyaca is not only Bogotá’s backyard, its also the breadbasket for this city of 7 million mouths and has fed it since the time of the Spanish.

After decades of having their human rights ignored the National Agrarian Strike with its epicenter in Boyaca was a last resort to get urbanite Colombians to pay attention: the countryside is in crisis so consumers can save a few pesos at the supermarket.

The strike had abated the day before and Tunjas Cathedral was packed with people who came to see three of the movements leaders who fought against forces far greater than themselves: the Colombian government castrated by consecutive Free Trade Agreements with foreign powers, the United States that provides the country with billions of dollars in military aid (and expects its back scratched in return) as well as omnipotent multinationals like Monsanto.

Their names were Florentino Borda, Walter Benavides, and César Pachón and they spoke to the gathered mass in front of a banner stating, “Thankyou for believing in the #RevolutionOfTheRuanas”

The name of the Indian woman was Kasturba Mohandas Gandhi and the priest recounted a question once asked to her about the man she married who brought the British Empire to its knees.

Her reply: “I did not marry a man,

I married a cause.”

This is the story of Boyaca’s cause.

The Seeds of Discontent

Before dawn 12 hours earlier a man they call Pacho from the nearby town of Paipa rigs his car with a speaker and microphone transforming it into a mobile soapbox.

Before dawn 12 hours earlier a man they call Pacho from the nearby town of Paipa rigs his car with a speaker and microphone transforming it into a mobile soapbox.

Mist hangs heavily over the back roads that bend up the mountainside and visibility is limited but Pacho dodges the severed trees that had, up until a few days before, blocked all entries and exits to the town.

With steering wheel in one hand and a microphone in the other Pacho shouts out the first names of those who cut the trees and blocked the roads with aggressive threats of force – they are potato farmers and they are invited to a Town Hall Meeting that morning where farmers get to discuss the strikes resolution with Florentino Borda, Walter Benavides, and César Pachón.

Flour & Barley: Because Cocaine is not an Option

Pacho has gained a measure of success in his life and now runs a warehouse full of farming goods from fertilizer to cattle feed and tools both big and small to work the land. But sales have bottomlined, purchases are being made on credit, and customers he counts as friends are struggling to survive.

“This conflict comes from much further back than Santos or Uribe and the TLC” says Pacho referring to Colombia’s Free Trade Agreement with the United States in his history lesson of Boyaca.

In the 1970’s the crop of choice for the province was barley until big beer breweries with factories in the province began using imports from the US. The farmers switched to wheat which was used in bakeries across Boyaca but subsidized wheat and flour from the US undercut competition in the 80’s.

Over the following decades everything from contraband Ecuadorian potatoes to European imports of powdered milk made it harder for Boyacenses to do business.

Over the following decades everything from contraband Ecuadorian potatoes to European imports of powdered milk made it harder for Boyacenses to do business.

In other parts of the country these Fair Trade Agreements that flooded the market with cheap foreign imports forced farmers into growing the one Colombian crop with insatiable international demand:

the Coca leaf.

Boyaca’s too cold for Coca.

“We don’t have politicians that protect the community, they are selling the country and the farmers are fed up.” Pacho says as the car climbs up above the mist for a view of Boyaca’s spectular valleys.

“The same state that forgot about the potato farmers is facilitating the multinationals so that they can sell more at subsidized prices.”

Potato Farmers Do Not Want Monsanto Seeds

Three paperos or potato farmers come to greet us, “this land makes good potatoes but what kills us are the importations, they don’t let us compete and now we are broke” says community leader Alexander Camargo.

Three paperos or potato farmers come to greet us, “this land makes good potatoes but what kills us are the importations, they don’t let us compete and now we are broke” says community leader Alexander Camargo.

“You dont sell potatoes,” he says, “you give them away.”

Its not a lack of creativity or initiative that bankrupted the potato farmers of Paipa.

For years they have gone to the mayor with plans to help return their industry to profit but the municipal government ignored them. One such plan was a seed bank that Alexander Camargo and Luis Cipaguata dreamt of creating called Crops from a Cold Land.

After Colombia signed the TLC with the United States storing seeds became a criminal offence. Farmers that followed the tradition of their great grandfathers became criminals under new laws enforced with fines or imprisonment. Saving seeds threatened the bottomline of Monsanto.

[quote]”We need to buy foreign seeds but they are too expensive, we want to certify our own seeds” says Camargo, “if we cannot save our own seeds then they have us screwed.”[/quote]

Catastrophic Acts of God vs Government Pacts: MercoSur, TLC

The nearby town of Santa Teresa has felt the destructive nature of these Free Trade Agreements with the US and South American countries under the MercoSur umbrella as hard as 3 floods that devastated the area in 2.5 years.

“When the government took the barley off us we had to look for a different crop, some went for potatos, others for milk or onions,” says Wilson Pulido a representative for the region.

“When the government took the barley off us we had to look for a different crop, some went for potatos, others for milk or onions,” says Wilson Pulido a representative for the region.

“After the floods destroyed everything everyone’s in debt and then the government floods us with Peruvian onions, MercoSur, the TLC.” he says.

“Now it costs 55,000 pesos to get a load of onions but we have to sell that load at 20,000 pesos, we are losing 70 percent on every load”

Back in Paipa Pacho drives down the valley to ready himself for the Town Hall Meeting and tells me, “What other choice do the people here have? They are honest, they don’t know how to steal, they aren’t guerrillas, they only want to work with dignity to get a better quality of life for their families”

You can only step over peoples human rights for so long until they have nothing left to lose and the stoic Boyacenses had nothing left to lose. They took the roads.

How The Movement Spread

1. The Watercooler of Dissent: Fruit & Vegetable Markets

Colombia’s National Agrarian Strike started as grassroots as it gets: in fruit and veg markets across Boyaca where farmers and sellers had been swapping stories of dwindling profits and soaring losses for years.

It was here Pacho says: “farmers communicated and organized every single wednesday”

2. Protest Leaders Organize While President Santos Laughs

On May 7th 2013 representatives for farmers convened in Bogotá to alert the the government about the crisis in its agricultural sector. Speeches on Youtube by César Pachon and Florentino Borda show how their microphones are cut which was considered incredibly condescending by farmers.

The government gave them empty promises but the congregation served an important purpose to Pachón and Borda because they were able to network with other sidelined farmers from provinces across the country to coordinate the next strike.

In August 2013 when the National Agrarian Strike began comments by President Santos deliberately belittling the size of the protests infuriated Boyacenses long fed up with their rights being ignored.

“There were only 20 or 30 people blocking the roads” says Pacho, “but when Santos said ‘this so called national strike doesn’t exist‘ overnight we trippled in size.”

The Boyacenses wanted to send a message: YES WE EXIST.

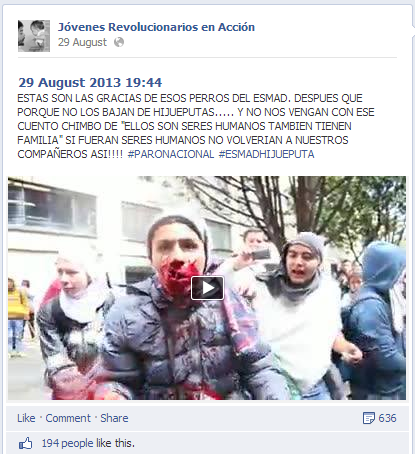

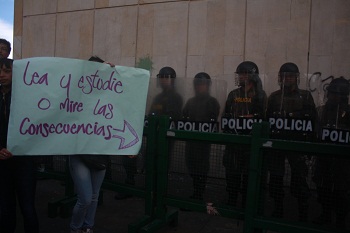

3. Citizen Journalists Shoot Police Human Rights Abuses

To beat Boyaca’s farmers into submission the Colombian government sent a largely undisciplined, downright violent, and universally feared force of ESMAD Riot Police to stop the protests.

What happened next would shock the western world but comes as no surprise to your average Colombian: these trigger-happy storm troopers dressed like Darth Vader vigilantes began looting and pillaging the countryside.

In the village of Barranco 10 minutes outside of Tunja a potato farmer named Ernesto Torres was selling black coffee to protestors blocking the via Bogotá a mere 100 meters from his home. When the ESMAD arrived protestors panicked and ran up past Torres’ house and into the hills but the police gave up chase and looted the potato farmers’ home instead.

That night the ESMAD broke Torres’ two motorbikes, tipped over a gallon bucket of honey, stole 3,000,000 pesos he had set aside to buy pesticide, smashed the windows and left spent teargass grenades on his childrens bunkbeds.

[quote]”We left the door unlocked because its safe in the countryside, we never thought something like this could happen in Boyaca,” says Ernesto Torres, “Thank god the children were with my father.”[/quote]

“I believe the ESMAD made us stronger” César Pachón told me explaining how the deluge of videos by Citizen Journalists documenting human rights abuses by the ESMAD caused public outrage and garnered the sympathy of Colombian’s from the city.

4. The Town Hall of the Future: Red Boyaca

In Paipa’s Town Hall the mood is a mix of elation and tense relief amongst the farmers gathered. Here Florentino Borda, Walter Benavides, and César Pachón give speeches about what Boyaca gained now the strike against the government had been resolved while citizen journalist Aida Castro films and tweets their points.

The sleepy town of Paipa, like many others in the province, have risen up in protest only once before in history: during the Battle of Boyacá in August 1819 that gained Colombia its independence from the Spanish.

This August 193 years later the Colombian elite are again facilitating foreign states as well as multinationals to plunder the countryside at the expense of the human rights of farmers and their families.

What has changed however is a phenomena mushrooming across South American cyberspace called the Town Hall of the Future – online meeting places like this brick and mortar Town Hall in Paipa were concerned citizens come to discuss important topics online.

Online Town Halls like Red Boyaca are the future in bringing people together to fight for their communities by holding human rights abuses accountable thanks to the courageous grassroots reporting by citizen journalists.

There is an old saying in this cold Colombian province: “Boyacenses don’t pray to God for good crops, they pray the neighbors crops will fail.” Now however for the second time in history the stoic Boyacenses are united but this time they are hyper-connected to each other and the rest of Colombia thanks to Citizen Journalism and the Town Halls of the Future.

[mc4wp_form]